The Benefits of Using a Rack to Keep Your Workbench Tidy

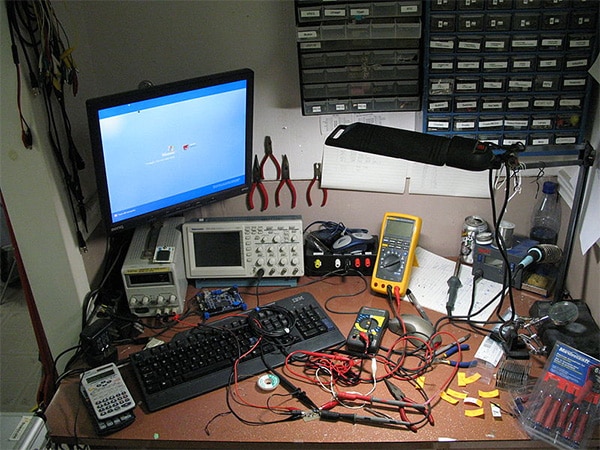

One common stereotypical image in the mind of the non-engineering public is that the work area of the typical design engineer is chaotic. Circuit boards and boxes are scattered semi-randomly around the bench along with a rat’s nest of cables connecting everything. Though many prototype test benches are reasonably neat and organized, there is an element of truth to this cliché—especially as the development cycle progresses.

So why should benches be such a mess? As with almost all engineering questions, there is no “one-size-fits-all” answer. I say this as a former hands-on engineer who has also visited dozens of EEs at their benches while they were working on advanced projects. Sooner or later, the prototype bench often ends up a mess, even though the design team starts out with the best of clutter-free intentions (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Some engineering workbenches are relatively clear and clean with only a few pc boards, meters, other instruments, and test leads. (Image source: Wikipedia)

Figure 1: Some engineering workbenches are relatively clear and clean with only a few pc boards, meters, other instruments, and test leads. (Image source: Wikipedia)

This happens as more instruments and test leads are needed; temporary and improvised fixtures are used to simulate inputs and operating conditions; larger battery packs are added for longer-running tests; and documentation—datasheets, user manuals, hand-written notes and reminders, and “DO NOT TOUCH” admonitions—pile up.

Is clutter detrimental to product development?

Does this clutter lead to inefficient product development, debug, and assessment? The answers range from “it sure is” to “it’s not a problem for me”, and there are examples to back up all of these contentions.

Look at the super-cluttered yet highly productive bench of the late, brilliant analog electronics engineer Jim Williams of Linear Technology Corp., now part of Analog Devices (Figure 2). After his untimely passing in 2011, his legendary workbench was displayed—exactly as he left it—in a special 2012 exhibit at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, CA1.

Figure 2: The legendary analog circuit design genius Jim Williams looking up from his famous, hyper-cluttered workbench at Linear Technology Corp. (Image source: Mercury News)

Figure 2: The legendary analog circuit design genius Jim Williams looking up from his famous, hyper-cluttered workbench at Linear Technology Corp. (Image source: Mercury News)

He consistently developed innovative circuits and systems at what looked like a hoarder’s stash of random components and instrumentation. The justification for this, at which Jim only winked slyly when I visited him a few months before he passed away, was that the mess was the way he liked to work, and it also discouraged “temporary” borrowing of test equipment by his co-workers.

Still, Jim’s bench may be the exception: for most engineers and projects, a neat work area—though not necessarily obsessively ultra-neat—is increasingly a necessity rather than a preference. With the ever-higher frequencies of even modest circuits such as 2 megahertz (MHz) DC/DC switching converters and multi-gigahertz RF circuits, having wires and connectors in suspension in mid-air is begging for trouble at all phases of the prototype and breadboard stage.

There’s an easy solution

It’s nice when there is a straightforward, hassle-free, low-tech solution to a problem. In the case of benchtop clutter, there is one: the 19 inch rack.

There’s nothing new about the use of racks in engineering, of course. They are often used for large automated test equipment (ATE) set-ups, for example. Nearly all instruments such as oscilloscopes, waveform generators, and spectrum analyzers are directly rack mountable, or can be racked with a modest add-on kit.

Nonetheless, I have rarely seen these instruments in a rack at the engineer’s bench. There could be any one of several reasons for this absence: perhaps it’s due to the incremental nature of the clutter growth; or having one might send a subliminal but premature message to management that “we’re almost finished”; or having a nearby rack requires stringing numerous cables between the rack and the prototype under evaluation, which is often inconvenient.

But racks come in a variety of types and configurations that can overcome these concerns. There’s the heavy-duty, double-frame 86 inch (in.) high rack such as the Hammond Manufacturing C2F197823LG1 full-height rack (Figure 3).

Figure 3: This double-frame, full-height 19 in. rack can take a large amount of test equipment off the designer’s bench. (Image source: Hammond Manufacturing)

Figure 3: This double-frame, full-height 19 in. rack can take a large amount of test equipment off the designer’s bench. (Image source: Hammond Manufacturing)

There are also single-frame units for lighter total load weight such as the Bud Industries RR-1264-BT which is nearly as high as the C2F197823LG1 at 70 in., and which offers somewhat easier access to the front and back of its contents (Figure 4).

Figure 4: A single-frame full-height rack can also clear the test bench while offering easy access to front and back sides of the mounted units. (Image source: Bud Industries)

Figure 4: A single-frame full-height rack can also clear the test bench while offering easy access to front and back sides of the mounted units. (Image source: Bud Industries)

These full-height floor racks may be too much for the bench-top development scenario, but there’s an attractive alternative: a shorter, 11 in. high rack such as the Hammond Manufacturing RCHV1900817BK1, which can be placed on the corner of the benchtop rather than next to it (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Even a modest 11 inch high rack placed directly on the corner of the workbench will help clear the clutter and encourage discipline. (Image source: Hammond Manufacturing)

Figure 5: Even a modest 11 inch high rack placed directly on the corner of the workbench will help clear the clutter and encourage discipline. (Image source: Hammond Manufacturing)

Racks are not just for mounting of vendor-supplier instrumentation units, either. Many years ago, I was involved in the design of a controller for a large electromechanical test frame which had some frame-mounted switches that tripped when the piston’s excursion exceeded a set value. For initial testing we needed to emulate the limit switch closure but did not want to energize an actual frame.

The solution was simple. One of our team’s engineers had a military surplus radio toggle-switch array about 7 in. wide and 2 ½ in. high (Figure 6). We used these switches (which had the smoothest toggling action I have ever encountered) to allow the software engineer to easily initiate a limit-switch event while sitting at the keyboard, and the set-up worked well.

Figure 6: This array of military surplus toggle switches was used to simulate the action of limit switches on a load frame during an ongoing product development process. (Image source: Bill Schweber)

Figure 6: This array of military surplus toggle switches was used to simulate the action of limit switches on a load frame during an ongoing product development process. (Image source: Bill Schweber)

However, as the project proceeded, there were more instruments, leads, power supplies, and fixtures on the bench. Soon that set of toggle switches was hard to find and getting tangled in everything. The solution was straightforward: we placed a tabletop 19 in. rack on the corner of the bench and had the in-house model shop make a narrow rack panel with a cutout for the toggle switch array, thus giving it a fixed home. We even took further advantage of the new rack by mounting a few other small instruments in it and added some full-width shelves so we had a place for small boards which could not be easily rack mounted. The result was greater efficiency, fewer foolish mistakes, and fewer items disappearing when we weren’t looking!

There’s an aspect of longevity in the rack story. The 19 in. rack as we know it was developed about 100 years ago, according to the well-written Wikipedia article “19 inch rack.” While Wikipedia postings are not necessarily definitive or always completely accurate, they are often a useful starting point: this one references a 1922 article, “Telephone Equipment for Long Cable Circuits” from the venerable Bell System Technology Journal which has been scanned and is available at the Internet Archive, so you can see the rational and specifics of rack development from the primary source.

Note that in the first half of the 20th century, the market position and technical expertise of the Bell Telephone System with respect to design, manufacturing, research, and installation was so dominant that they could set de facto industry standards, and often did.

If your initial acquisition of instrumentation and equipment did not include a rack-mount kit, it is still worth consideration as your project moves ahead. Even a basic small form factor power supply unit (PSU) can migrate from the benchtop to a nearby rack. For example, the XP Power PLS600 series of benchtop PSUs can be easily put into a rack using the vendor-supplied PLS600 Rack-Mount Kit which supports mounting of two of these PSUs side-by-side (Figure 7).

Figure 7: The XP Power PLS600 Rack Mount Kit eases installation of a single PLS600 unit or a side-by-side pair in a standard chassis equipment rack. (Image source: XP Power)

Figure 7: The XP Power PLS600 Rack Mount Kit eases installation of a single PLS600 unit or a side-by-side pair in a standard chassis equipment rack. (Image source: XP Power)

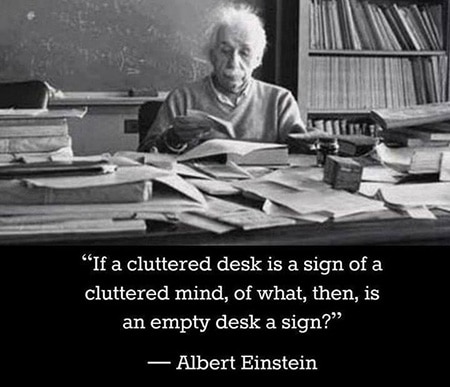

Don’t let Einstein’s wit compromise your productivity

You may have seen the “clever” saying attributed to Albert Einstein on a poster similar to the one shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8: This quote attributed to Albert Einstein does not necessarily also apply to product design, development, and debug. (Image source: Quora)

Figure 8: This quote attributed to Albert Einstein does not necessarily also apply to product design, development, and debug. (Image source: Quora)

Maybe that’s the situation for advanced physics, but for hands-on engineers at the bench, it’s not. This is made very clear in the excellent book “Debugging: The 9 Indispensable Rules of Finding Even the Most Elusive Software and Hardware Problems” (Figure 9). In this indispensable work, author David J. Agans details the many benefits of having an organized work area with clear documentation, so you know what you have to work with and what you have done.

Figure 9: Debugging is among the most difficult engineering skills to master, and this book is a very insightful resource into strategies and tactics for hardware and software debugging. (Image source: Amazon)

Figure 9: Debugging is among the most difficult engineering skills to master, and this book is a very insightful resource into strategies and tactics for hardware and software debugging. (Image source: Amazon)

It only takes one bad experience of wasting hours, days, or weeks trying to find and fix a bug within an inefficient and misleading benchtop arrangement or finding out that the problem was in the test set-up and not the prototype. To make it clear: an organized workbench is your partner, and a low-tech rack can help make that happen.

Reference

1 – Mercury News, “Jim Williams’ workbench captures his life and Silicon Valley”

Have questions or comments? Continue the conversation on TechForum, DigiKey's online community and technical resource.

Visit TechForum