More Semiconductor Sources Are Coming, But it Will Take Time

We know that for the electronics industry, in particular, the cost of supply chain vulnerabilities has been writ large in terms of the semiconductor industry. That’s why it’s hard to stand by and watch as the semiconductor producers grapple with a spike in demand, combined with a series of unexpected events that hamstrung production and delivery. Added to that, fearful OEMs have stockpiled chips. What has become most clear is that semiconductors are critical to the health of today’s global economy—so shortages can’t be ignored.

The semiconductor landscape

Currently, a notable shortfall of less advanced chips is plaguing the electronics industry—and I don’t foresee an end to the shortfall arriving quickly. And I’m not alone. "We believe semi companies are shipping 10 percent to 30 percent below current demand levels, and it will take at least three to four quarters for supply to catch up with demand, and then another one to two quarters for inventories at customers/distribution channels to be replenished back to normal levels," said Harlan Sur, an analyst with J.P. Morgan, in a note to clients.1

I have seen some reports and have seen enough over my decades of covering the electronics industry to expect chip makers to put their attention on higher-margin, cutting-edge chips, leaving a shortfall of more common and less complex chips. Meanwhile, shifts in consumer demand have caused demand to outstrip supply on the low end. Semiconductor manufacturers are scrambling to reallocate production and add capacity—an activity that can take years.

And, from a variety of sources, I gather that demand is surging—with clear shifts related to the pandemic. “Global semiconductor sales during the first two months of the year have outpaced sales from early in 2020 when the pandemic began to spread in parts of the world,” said John Neuffer, SIA president and CEO. “Sales into the China market saw the largest year-to-year growth, largely because sales there were down substantially early last year.”

Here are some numbers: Global semiconductor industry sales were $39.6 billion in February 2021, an increase of 14.7 percent over the February 2020 total of $34.5 billion, but 1.0% less than the January 2021 total of $40.0 billion. Monthly sales are compiled by the World Semiconductor Trade Statistics (WSTS) organization and represent a three-month moving average.

![]() Figure 1: Global semiconductor industry sales were $39.6 billion for the month of February 2021, an increase of 14.7 percent over the February 2020 total of $34.5 billion, but 1.0% less than the January 2021 total of $40.0 billion. Monthly sales represent a three-month moving average. (Image source: WSTS)

Figure 1: Global semiconductor industry sales were $39.6 billion for the month of February 2021, an increase of 14.7 percent over the February 2020 total of $34.5 billion, but 1.0% less than the January 2021 total of $40.0 billion. Monthly sales represent a three-month moving average. (Image source: WSTS)

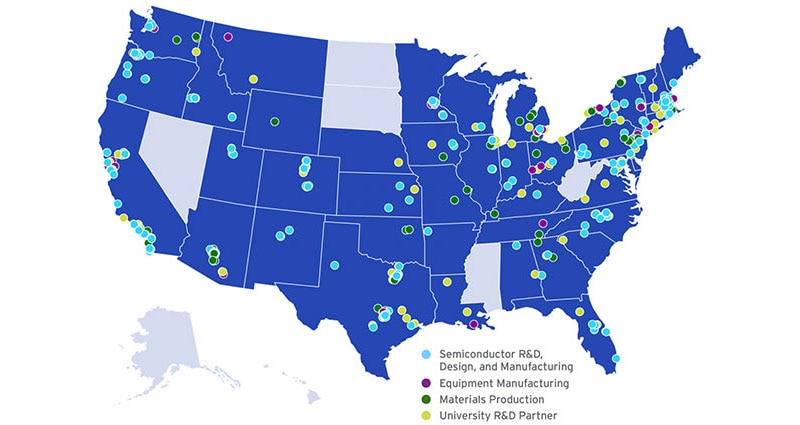

Meanwhile, semiconductor manufacturing capacity is concentrated in China and East Asia. It’s no secret that these areas of the world are subject to a variety of risks, ranging from political unrest to natural disasters. Currently, about 75 percent of semiconductor manufacturing capacity, as well as key material suppliers, are located in this region, according to the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA).2 All of the capacity of sub-10 nanometer (nm) logic semiconductor capacity is located in Taiwan (92 percent) and South Korea (eight percent).

History has taught me that limited sourcing (whether limited to a certain manufacturer or a geographic area) has inherent risk. We saw that when Japan suffered an earthquake in 2011 that pushed up DRAM prices. And that's just one example. Today’s semiconductor landscape is risky. “There are more than 50 points across the value chain where one region holds more than 65% of the global market share,” the SIA added. “Some of these single points in the value chain could be disrupted by natural disasters, infrastructure shutdowns, or geopolitical conflicts and may cause large-scale interruptions in the supply of essential chips.” The problem is that this goes beyond shipping or receiving the latest TV or washing machine.

The bigger implications

Chip shortages have the potential to wreak broader economic havoc in a world where the global pandemic has already caused notable economic contraction. For 2020, gross domestic product (GDP) across every country was down, according to the World Bank’s recently released Global Outlook for 2020 and 2021.3

![]() Figure 2: Countries experiencing contractions in per capita GDP will reach the highest level since 1970 this year. (Image source: World Bank Global Outlook for 2021)

Figure 2: Countries experiencing contractions in per capita GDP will reach the highest level since 1970 this year. (Image source: World Bank Global Outlook for 2021)

The shortage, unfortunately, comes at a time when further advancements in semiconductor technology are more essential than ever to enabling a new wave of transformative technologies. These include artificial intelligence (AI), 5G, autonomous and electric vehicles, and Internet of Things (IoT) solutions deployed at scale with a myriad of smart connected devices. I see this as a double whammy: a shortage at a time of greatest need.

I’m glad governments are (finally) concerned that a shortage of components could slow post-pandemic recovery for some industries, making it impossible to meet demand and so preventing them from taking advantage of expectations for increased consumer spending in coming months. General Motors, for example, announced plant shutdowns related to a lack of availability of semiconductors. Economists, meanwhile, are concerned that higher chip costs will translate into higher prices throughout the economy and stoke inflation. However, being concerned doesn’t really help, without fast action. So far, that’s been lacking.

United States and European Union seek technology independence

Nations that currently provide a home for semiconductor manufacturers have a strong track record of providing incentives and other government support to the industry. I have watched over the decades as manufacturing has shifted around the world to capture lower wages, better tax benefits, and other incentives, as well as market access.

It’s also encouraging that the United States (US) and the European Union (EU) are looking for ways to lure capacity to their native shores to address ongoing capacity concerns. Both the US and the EU have described bold plans to be more independent, particularly in the case of advanced technologies.

Here in the US, the FY2021 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), enacted on January 1, promises billions of dollars in new federal support for the US semiconductor industry, most notably tax credits and grants for the construction of new domestic manufacturing facilities. The related Creating Helpful Incentives for Producing Semiconductors (CHIPS) for America Act was enacted in December by Congress. This is notable because, at this time, only about 12.5 percent of semiconductors are made in the United States.4 Those heavy subsidies and tax breaks in other geographies I mentioned earlier have taken their toll.

More recently, President Biden introduced an infrastructure plan that includes initiatives to strengthen the semiconductor supply chain. The plan includes:

- $50 billion for semiconductor research and manufacturing.

- $50 billion to create an office at the Commerce Department on the US’s industrial capacity and support for the production of critical products.

- $50 billion for the National Science Foundation to create a technology directorate that would focus on key areas such as semiconductors.

These moves may help the US make progress, but experience tells me it will take time. A lot of time. Meanwhile, in May 2020, TSMC announced that it will build a new high-end fab in Arizona, but that won’t come online until 2024, at the soonest. It will use the company’s 5 nanometer (nm) process and promises an output of up to 20,000 wafers per month. TSMC believes that it will cost $12 billion to build, making it the most expensive fab ever built in the US.

The EU, last month (March), put forward its Digital Compass plan, which includes investing about $166 billion of its coronavirus recovery fund into the digital sector over the next several years. As part of the initiative, the EU hopes to produce at least 20 percent of the advanced semiconductor (i.e., sub 5 nm) used worldwide by 2030.

Conclusion

Semiconductor chips are critical to the global digital economy, and it’s clear that multiple sources for semiconductors are required. However, shifting production will require a forklift upgrade for everything, from education to immigration, so it will not be an easy task. We need to start thinking holistically about how to ensure that the industry will thrive internationally and domestically, and ensure that the chips we need not only get made but securely shipped.

There is an enormous effort required to address the risks associated with chip security and supply disruption that comes as the price of too much dependence on a single source or geography for semiconductor manufacturing. Designers naturally seek multiple sources for their components, where possible, and we should be helping them at a global level. This perfect storm of supply vs. demand challenges will need a similar alignment of positive forces to steer—and propel—us in a new direction, for all our sakes.

References:

3 – https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/33748/211553-Ch01.pdf

4 – https://www.semiconductors.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/2020-SIA-State-of-the-Industry-Report.pdf

Have questions or comments? Continue the conversation on TechForum, DigiKey's online community and technical resource.

Visit TechForum